Thank you to everybody who came to our second discussion on the 23rd of September! Lili and I decided early on that we were keen to discuss womanhood early on, and we were both had a wonderful time hearing everybody’s ideas and experiences. The main question we focused on was: Is there anything that all women have in common? And is it worth looking for such a shared experience?

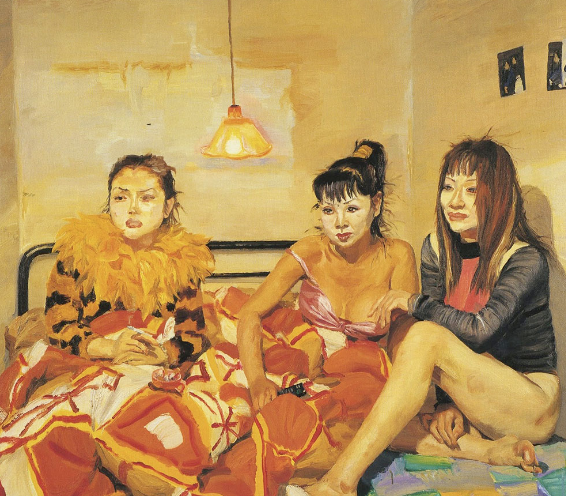

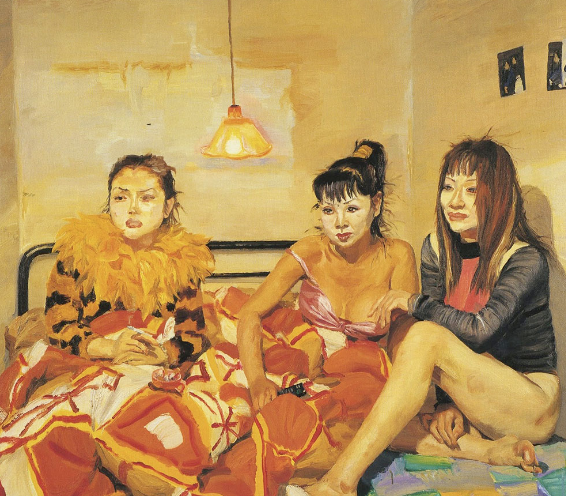

Liu Xiaodong | 刘小东 – Three Girls Watching TV, 2001

Being ‘Made’ a Woman

It was difficult to begin our discussion on womanhood given that the topic is so immensely broad. The reading I chose as a starting focal point was De Beauvoir’s chapter on Childhood in ‘The Second Sex’. We spoke briefly about De Beauvoir’s claim – that women are created through gender socialisation. We noticed, immediately, that this claim was exclusionary: those who were not socialised into womanhood, by this definition, could not be considered women. Being exclusionary of trans individuals, in our view, makes the theory inviable, but we were unsure of where to go from this point.

In order to give our discussion a stepping off point, I spoke briefly about the philosophical background to defining womanhood. We noted that while De Beauvoir’s point is unsuitable for our modern understanding of womanhood, it served as an important and significant rebuttal against bio-essentialism about gender, which was the dominant view of her era. I spoke about bio-essentialism as being a reductive claim – that biological factors are the sole determinants of gender and gender characteristics. The idea that gender results from socialisation contrasts this idea, undermining the idea that gender categories, and similarly, gender hierarchies, are innate and unchangeable.

The Complexity of Womanhood

Another group member introduced the idea that being viewed or treated as a woman, and self-identifying as a woman, are distinct concepts. I connected this to a theory presented by Katharine Jenkins, who suggested we distinguish between ‘women’ as a class and ‘women’ as an identity. Jenkins’ definition of womanhood as an identity is defined by one’s internal map – the set of rules and behaviour one applies to oneself. A number of problems with this issue were apparent, such as the complexity of the maps each individual ascribes to themself, which may make it hard to isolate the associated gender of a person’s internal guidings. We noted, additionally, that there are many women who feel no internal concordance or affinity to their gender, but instead the identity as a ‘badge of survival’ or reaction to the harmful socialisation they have been subjected to, and that these women ought to be included in the definition of women.

In response to this thought, one group member raised the idea that the complexity and heterogeneity of womanhood was so vast that it felt unlikely that we would be able to accommodate all instances of womanhood within a single definition, harkening back to our original question. We moved, then, to the second part of the question, which asked whether there was value to trying to find a commonality between all women. Some group members voiced feeling as if the search to find shared characteristics between women would end up ‘boxing us in’ to certain stereotypes, such as being highly communicative or emotional. Another group member raised the idea that it was not recognising differences between men and women which created a gender hierarchy, but the valuing of feminine-associated characteristics above masculine-associated characteristics. I suggested that both of these claims, the difference and the devaluing, are a necessary part of forming a gender-based hierarchy. We also questioned whether the idea of ‘true’ differences between genders was compatible with our feminism, ultimately coming to the conclusion that supporting stereotypes about gender-associated characteristics could serve the purpose of giving future discrimination a ‘foothold,’ so to speak, and therefore we would prefer to avoid it.

Bimbo Feminism

Earlier in the discussion, in reference to the multitude of ways that womanhood can occur, one of the group members spoke briefly about ‘bimbo feminism,’ which sparked a separate, interesting conversation. Bimbo feminism describes a movement wherein individuals of any gender perform hyper-feminine, appearance focused behaviours, often playing into the stereotype of an unintelligent superficial ‘bimbo’ as a form of parody. Several group members felt immediate trepidation about the movement, but struggled to pinpoint exactly what made them uncomfortable.

An immediate criticism which was raised was that since many women do not fit into the traditional ‘bimbo’ stereotype, this made the movement inaccessible to some. Speaking as an individual who views themself a part of the ‘bimbo feminism’ movement, I disagreed with this idea, as similarly to other forms of parody, the idea of portraying things discordantly to how others expect them is an important part of the performance, for instance, wearing hyper-feminine outfits while refusing to shave one’s body hair. Additionally, myself being both disabled and plus sized would exclude me from fitting the traditional bimbo stereotype, yet it enhances my performance of femininity as parody. We also considered whether the movement was safe to engage in for some individuals but not others, but noted that parodying a derogatory stereotype about women is not particularly safe for anybody, and that so long as disparities in safety between different groups is generated externally, not internally, to a movement, these disparities should not count against it. However, this once again highlighted the importance for us of maintaining intersectional mindfulness in all of the spaces we exist in.

A fallacy we found as a thread through our concerns was the idea that a performance of femininity was a suggestion or pressure of some kind, for other women to act in a similar way. We acknowledged that these forms of competitive femininity exist, but do not encompass all gender performances. In fact, I noted that ‘bimbo feminist’ communities, similarly to the appreciation of mascs by femmes in lesbian communities, explicitly appreciate and praise other forms of gender performance. Once we had deconstructed our collective trepidations about the movement, a couple of group members noted the heightened resistance to bimbo feminism in particular, both within themselves and larger feminist groups. I spoke my personal opinion, which is that misogyny is an incredibly pervasive force, and therefore openly accepting and subverting feminine characteristics draws more criticism than rejecting these characteristics altogether. As we had spoken about earlier, gender hierarchies rely on both assumptions: that there are true differences between men and women, and that the ones associated with femininity are inferior. Feminists who reject inequality on the basis of the first, but not the second, claim being incorrect are bound to retain a negative view of feminine associated characteristics.

Thank you again to everybody who came, everybody who is reading, and who might join in future! Lili and I look forward to our next discussion, which will focus around Masculinity. Until then, keep up the good fight,

Robin

Leave a Reply