Thank you everybody who came to the discussion on intersectionality on 9/9/23! Lili and I were so glad to be able to talk through these ideas with everybody. I thought it would be nice for our inaugural post on the Works in Progress website to be a write-up of what we discussed in the group. Please don’t be intimidated if this seems quite dense or I am using obscure language – it is just because I am trying to condense down a lot of nuance! Still, if there’s anything that is a bit too unclear, please contact me and let me know 🙂

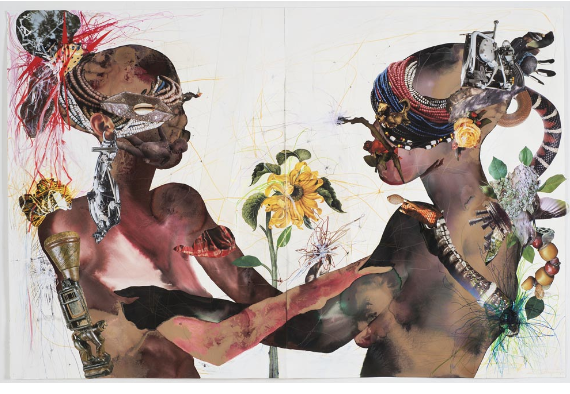

Wangechi Mutu, ‘You are my sunshine’, 2006.

Our first discussion group was centred around the topic of intersectionality, as we thought it was wise to start with a topic we wanted to inform our future discussions. The question we set out to focus on was “what does it mean to centre marginalised voices in our discussions around feminism?” but we found that there was plenty to say even without us referring back to the question! Our conversation spanned many nuanced topics, such as the practical consequences of marginalisation within feminism, and what it means to speak for others.

The importance of intersectionality

We started our discussion by talking about some of the ideas expressed by the Combahee River Statement, which was the central reading for the week. One group member began by noting the Collective’s rejection of the Separatist movement, which was a feminist movement prevalent in the 70s and 80s which advocated for the total separation of the sexes. The statement, written by black lesbian feminists, argues that this policy does not accommodate those whose struggles against other forces (such as racism and capitalism) required them to maintain solidarity with the men in their movements. We briefly looked at separatism as a case study of a non-intersectional feminist theory, asking ourselves what other groups may have been overlooked in the development of a separatist feminism. In doing so, we noted that separatism is inherently binary and therefore is not properly inclusive of those who fall outside of the gender binary, and is also unlikely to practically accommodate binary trans individuals. We also noted that women who are working class are the least capable of establishing financial independence from men, and similarly, disabled women are often dependent on practical help from men. We mentioned that, in addition to being non-inclusive, a serious implementation of the separatist movement would realistically result in the most marginalised women being left in a system without any feminist allies.

Another point which we acknowledged in our discussion of the separatist movement was the underlying notion that the problems of systematic gender-based discrimination result from innate differences between men and women, a thought which we unanimously disagreed with. We touched on the group’s mixed feelings surrounding involving men in feminist debate – while we all felt that men’s involvement in the movement is necessary, we all recognised times when we have censored our own thoughts around men. Provisionally, we decided to invite men into the space only once we felt we had established a space where we were able to speak comfortably and confidently with each other.

The scope of an intersectional feminism

These thoughts led to another interesting conversation on the scope of feminist theorising. Many of us felt strongly about focusing on community and grassroots activism within our feminism, yet weren’t sure how to consolidate this with a feminism which acknowledges and attends to intersectional identities. Our question was this: is it possible to incorporate the intersectional issues of racism, ableism, classism et cetera into a feminism which operates on the community level? We all felt the need to be committed to both a feminism which makes local community change and a feminism which is meaningfully intersectional, but felt that intersectionality denotes more issues than can be realistically tackled at the community level. In untangling this problem, we found it useful to distinguish between projects (practical steps taken within communities) and goals (overarching aims of a movement) within activism. While it is important that our feminist projects are compatible with the overarching goals of intersectional feminism, an intersectional approach does not mean that we have to undertake practical work towards every intersectional issue at once. However, ensuring that we are guided by intersectional thought when determining what projects we undertake in our community is necessary to practising intersectional feminism.

How do we use our voices?

As a group, we recognised the importance of using our voices to further intersectional aims both inside and outside of feminist spaces, and wondered how we should best recognise and consider the experiences of people who aren’t being included in the space. Here we touched on the complex topic of speaking for others. We acknowledged a number of nuances here – the idea of barriers towards speech for others, and the differences in how different speakers will be received. We spoke about the idea that those who are marginalised may be barred from speaking about their experiences due to lack of opportunity (potentially arising from lack of resources or advantages) and/or due to inflated possible consequences. For example, in speaking out about racist microagressions, a BIPOC individual risks putting themself in the line of fire of a person with racist beliefs, whereas there is less risk to a white person who speaks out similarly. We largely felt that in situations where a differently, or more marginalised, individual is barred from speaking about their experiences, the privileged individual ought to raise the possibility of another person’s perspective. Still, we felt that it was highly important to raise questions and considerations, rather than making statements about the impact to communities we aren’t a part of.

A group member also raised the idea that since privilege increases the likelihood of being listened to and taken seriously, this may be a further reason for privileged individuals to speak up for those who are more marginalised. We felt, however, that acting on the basis of prejudicial assumptions about credibility veered a bit too close to validating them, or perpetuating the cycles they’re a part of. With this in mind, we agreed that the extra resources privilege provides us with are best devoted to making spaces accessible and welcoming for those who otherwise wouldn’t have a chance to voice their perspectives, as a priority over voicing the possible perspectives of those more marginalised than us.

Emotional barriers to intersectionality

One of the final things we touched on in our discussion was the emotional barriers that occur within individuals as a barrier to accommodating others. We acknowledged that while the emotional responses that occur alongside oppressive actions are useful to understand, we ought to be careful to distinguish between acknowledging and holding space for certain emotional responses. We agreed that intersectional spaces are categorically not the place for individuals to work through prejudiced and prejudice-related emotions.

The last thing I will write about is how absolutely fantastic it was to be a part of this discussion. Everybody was incredibly respectful and thoughtful, and engaged with each other’s ideas supportively and in good faith. We found that a system of virtual hand-raising worked best for determining who would speak next, and that we found the group adapted well to switching between written and verbal discussion according to different individuals’ preferences. It was a pleasure to see the group find solutions to challenges as they came up. Much feminist discourse revolves around whether we, as feminists and/or as women, require shared experiences to unify us. I found, however, that our group came together with no presumptions about the experiences we may or may not share. Instead, our shared values and open curiosity towards each other’s thoughts and experiences was enough to create a truly collaborative discussion.

A huge thank-you again to everybody who came, and everybody who plans on coming in future,

Robin

Leave a Reply